Woodland Management Techniques

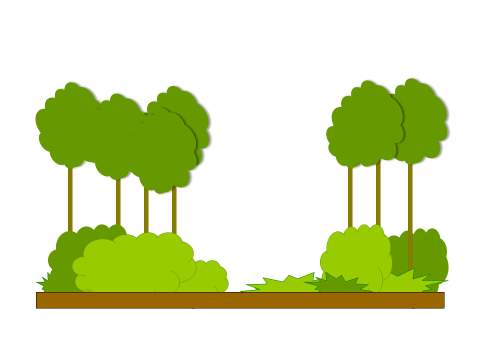

Improving the structure of even aged stands

| Method/Notes | Benefits for biodiversity and issues to watch out for |

|---|---|

|

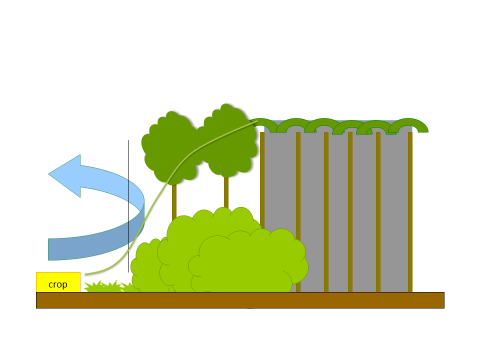

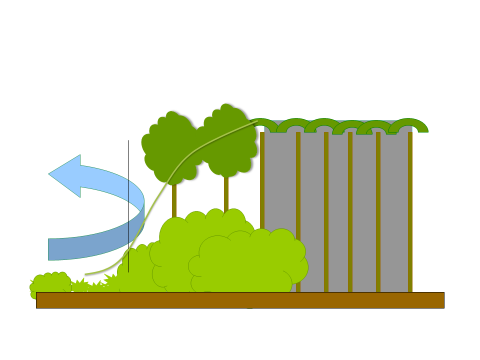

A major aim of habitat management in woodlands is to diversify their structure. It aims to create greater age and size class diversity in an even age stand of trees by felling groups or lines of trees at different intervals. It may also involve planting or natural regeneration and encourage growth of understorey shrubs and enhance deadwood. |

An opportunity for creating a range of habitats for species that need younger and older growth stages. |

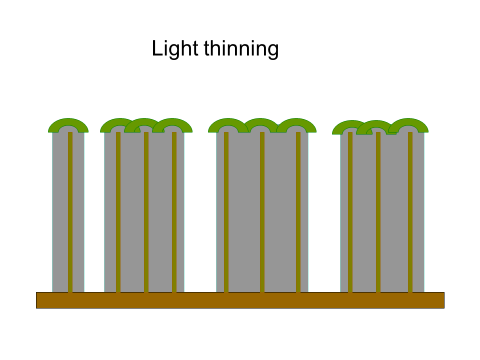

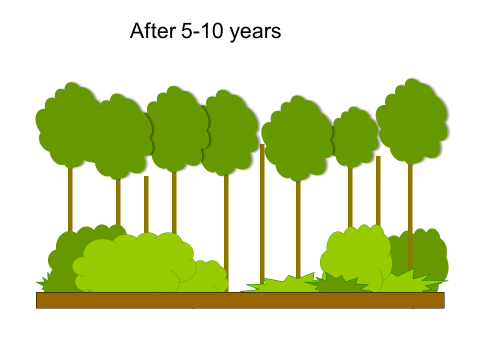

Thinning

Coppice

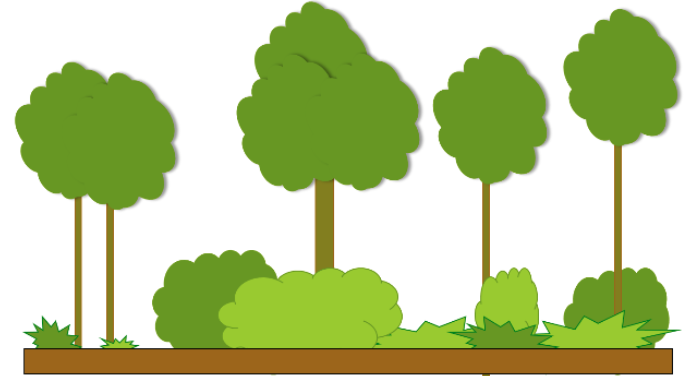

Continuous cover forestry (CCF) in broadleaf or conifer forest

| Method/Notes | Benefits for biodiversity and issues to watch out for | |

|---|---|---|

For further information, see the Continuous Cover Forestry Group website: www.ccfg.org.uk/ |

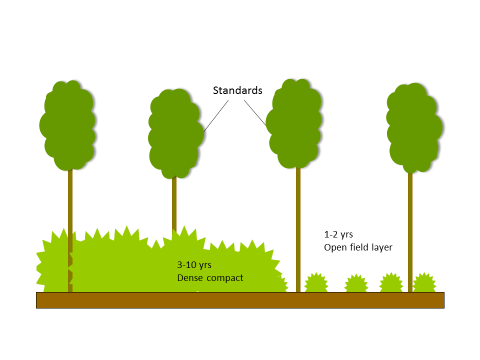

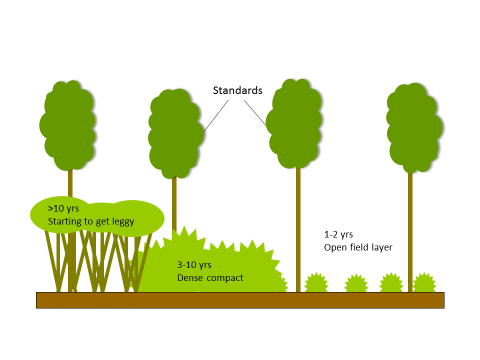

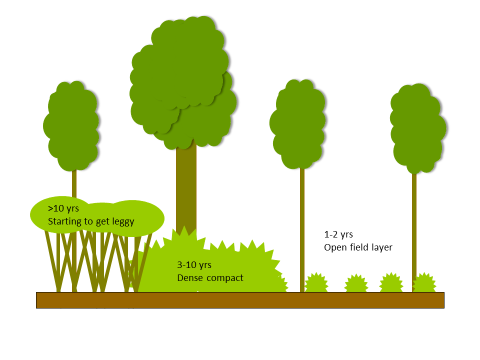

diagram: Nigel Symes, RSPB

|

The aim is to create more diverse forests both structurally and in terms of species composition. Some species are more likely to benefit from CCF approaches than others. For example, lowland broadleaved woodland birds could benefit from broadleaved CCF systems that provide sufficient canopy gaps and diversity of habitat structure. In certain areas CCF could pose a threat to species that rely on larger areas of open space within a forest, such as forest nesting nightjar and woodlark, butterflies etc. |

Restoring to native woodland

| Method/Notes | Benefits for biodiversity and issues to watch out for |

|---|---|

|

Restoring a native canopy from a non-native plantation e.g. a conifer plantation on an ancient woodland site (Plantation on Ancient Woodland Site, or PAWS). Not all such plantations are conifer, but can include e.g. beech plantations where beech is not native to the area. Further information is available from the Woodland Trust's publication 'Ancient woodland restoration - an introductory guide to the principles of restoration management' and from the Forestry Commission's publication 'Choosing stand management methods for restoring planted ancient woodland sites'. |

A wood does not have to be ancient in order to support threatened wildlife. Ancient woodland however contains some unique features which have developed over a very long period of time and cannot be found at younger sites. Ancient woodland soils contain unique communities of fungi, invertebrates and microbes. Woodland ground flora have evolved with these communities, and some depend upon them for survival. Some such plants, known as 'ancient woodland indicators' are only likely to be found in ancient woods, as they are very slow to spread to new sites. Some species of lichens, liverworts and mosses are also associated with ancient woodland, especially where old trees are present. Sites with numerous old and veteran trees, and high levels of decaying wood, are particularly valuable as these can support numerous species of fungi and invertebrates, some of which are extremely rare, as well as hole nesting species of birds and roosting bats. Restoration of PAWS often focuses on removing plantation trees, while retaining and favouring remnant features of the ancient woodland, such as ground flora or remaining native trees. Restoration to a native canopy can provide these species with suitable conditions to thrive again. Depending on the length of time since plantation and the level of soil disturbance that has taken place, ancient soil communities might also recover. Remnant features can be damaged where a drastic approach is taken to restoration, such as clear felling the plantation trees. A more gradual approach is usually most appropriate. |

Rides and edges

Dead and decaying wood

Water and wet features

Grazed woods

Broadly speaking, many upland, deciduous woods have traditionally been grazed by livestock in conjunction with the surrounding open mountain and moorland habitats. In contrast stock have typically been excluded from the majority of lowland woods to protect silviculture activities, with notable exceptions such as the New Forest. Until quite recently, the accepted ethos within the conservation sphere has been that stock-grazing in woodland is damaging to the habitat (other than in those traditionally grazed environments where some species are dependent on a certain level of grazing, and in wood-pasture parkland habitats). Livestock grazing may be inappropriate, for example in woods with waterlogged soils and steep slopes where poaching of the ground is likely to be an issue, or where there is already heavy browsing pressure from the local deer population. Inappropriate grazing can lead to soil erosion and compaction, damage to tree roots, loss of ground flora, it can suppress woodland regeneration, introduce alien or weedy species and can result in a simplified woodland structure. However in some cases light grazing can be better than no grazing, and can help to maintain woodland diversity. In the distant past, large herbivores were integral to the processes driving woodland development, and woodland succession may have been a much more dynamic process which provided more open, disturbed habitat within woods than has sometimes been envisaged. Many of our woodland species are associated with open woodland habitats rather than shady, closed canopy woodland. There is evidence that permanent removal of livestock can have a negative effect in some woods, for example where exclusion promotes dense bramble reducing light and seed germination opportunities, leading to minimal natural oak regeneration and also loss of lichens.

Fencing (to manage grazing)

Minimal intervention

Clearfell and Open Habitats

| Method/Notes | Benefits for biodiversity and issues to watch out for | |

|---|---|---|

|

.jpg)

image: Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)

|

Clearfell systems can provide temporary open habitats with some low scrubby vegetation, suitable for species such as nightjar, woodlark, some woodland ground flora and butterflies. As these areas are encroached by bramble and regenerating trees they can provide habitat for various scrub-loving birds, and invertebrates including butterflies; while young, thicket stages of replanted conifer or birch regeneration can support redpolls and tree pipits. Size and continuity of habitat can be an issue for many species of the earlier, more open stages of clearfell. Forest plans can be designed so that newly felled areas are located close to areas that are beginning to close over. For nightjar in particular, a continuity of clear-fells greater than 0.02 sq km in size is important, and where possible, creating a waved or scalloped edge to the coup will increase the length of foliage edge for feeding. Try to minimise disturbance in clear felled areas, e.g. due to public access, particularly dogs, as this can be detrimental to ground nesting birds. Likewise try to time operations outside the bird nesting season (May to September for nightjar). |